Eternal competitors for leadership in Asia, India and China have always been jealous of each other’s successes. Today, the rivalry between the two Asian superpowers, claiming dominance in the entire world, is reaching a completely new level—in space, where New Delhi and Beijing do not intend to yield to each other even by half a parsec.

China India space rivalry highlights how these BRICS nations are pushing boundaries in cosmic exploration.

Historical Rivalry Between Dragon and Elephant

It is now hard to imagine that in the 1950s, New Delhi and Beijing were considered close friends and talked about tight, friendly partnership. For example, in 1951, India turned a blind eye to the capture of Tibet by the Chinese army, limiting itself to formal statements—bilateral relations seemed more important to New Delhi. In those years, the slogan “Hindi-Chini bhai bhai!” (“Indians, Chinese—brothers!”) was proclaimed, which became very popular for a short time and appeared even a little earlier than “Hindi-Rusi bhai bhai!”. However, the Chinese Dragon and the Indian Elephant quickly became cramped next to each other—each country began to resolutely defend its rights to Asian leadership.

Already in 1962, an Indo-Chinese armed border conflict occurred when the Dragon and the Elephant began to divide the Himalayan foothills. Since then, the era of “bhai bhai” between Beijing and New Delhi has ended. Military personnel on the border of the two countries tensely watch each other, periodically there are reports of violations of the Indo-Chinese border in the mountains by military from the adjacent side. At the official level, India and China still talk about cooperation, but in fact, it is the PRC, and not Pakistan at all, that the Indian military doctrine considers as the most serious potential adversary.

However, neither of the two Asian giants dares to quarrel decisively in recent years. Moreover, the confrontation between these powers has now shifted to the field of economics. China has surged ahead as the “assembly shop” of the whole world, moreover capable of copying almost any Western technical novelty. India is still ahead in the field of offshore programming, has achieved success in the IT technology sphere. But the two Asian rivals also carefully monitor to match the image of a superpower: they have acquired nuclear weapons, aircraft carriers, are creating their own supersonic fighters and ballistic missiles—all this with a glance at each other. And now the Dragon and the Elephant intend to argue in space as well.

Cosmic Scale Vanity

This is how many observers in the world reacted to the news that China sent a man into space: in October 2003, the Chinese ship “Shenzhou-5” entered orbit with Lieutenant Colonel of the People’s Liberation Army of China Yang Liwei on board. It seemed then that Beijing simply decided to prove to everyone that it too could solve such a technical task. In world media, it was said that the Chinese spacecraft suspiciously resembles the good old Soviet “Soyuz”. That the flight did not solve any research or commercial tasks. The main outcome of this mission is only that the list of “cosmonauts” and “astronauts” now includes “taikonaut” as well.

Nevertheless, the Dragon achieved its goal: it became the third country in the world that managed to “send to the sky” a person without outside help. The forty-year lag of China from the USA and the USSR in manned flights, of course, makes itself felt. But today it is clear that China intends not to catch up, but to overtake the old space powers. The Chinese government, having at hand a set of powerful state enterprises, has made a serious bet on space, and the Chinese space program undertakes in a relatively short time to run through the same stages that American and Soviet cosmonautics passed through for many decades.

“Chinese fly into space not as often as Americans or Soviets in the era of acute space competition, but each of their new flights becomes not a repetition of the passed, but a qualitatively new stage in the development of their own space industry,” believes Indian journalist Vinod Trivedi.

Indeed, after the first manned flight, the space program of the PRC took a pause for two years, after which in October 2005, two people went into space on the ship “Shenzhou-6”: Fei Junlong and Nie Haisheng. In September 2008, three taikonauts ascended to orbit on board “Shenzhou-7”, one of whom, Zhai Zhigang, made a spacewalk, testing a spacesuit of Chinese development. Each launch was a new step in the pursuit race of the old space powers.

After that, the taikonauts took a pause again—the next ship, “Shenzhou-8”, flew in 2011 in unmanned mode and conducted a docking in orbit with the automatic orbital module “Tiangong-1”. After that, it was announced that this flight is preparation for creating its own orbital station. This preparation is in full swing: in June 2012, the ship “Shenzhou-9” with a crew of three people, including the first female taikonaut Liu Yang, conducted the first manual docking with the module “Tiangong-1”. The crew of this ship, again for the first time in the history of Chinese cosmonautics, transferred to the orbital module. And a year later, in June 2013, “Shenzhou-10” docked with this module, three taikonauts, including another woman—Wang Yaping, spent 15 days in space. On the approach—sending larger orbital modules “Tiangong-2” and “Tiangong-3” into space, and in the near future (2020 is named)—creating the first Chinese multi-module inhabited space station on orbit.

Jump into International Space

The deadline for creating a Chinese manned station in orbit—by 2020—is not accidental. It is by this time, as it is believed, that serious problems with financing may begin at the International Space Station. The Chinese side is ready to fill the gap if the ISS program is curtailed: Beijing has already stated that it will allow cosmonauts and astronauts from other countries to work on board its complex. If this happens, China will de facto head international orbital research. Although it is not clear whether the old space powers will agree to this.

The scale of China’s space program can be seen right on Earth—on Hainan Island in the South China Sea, where the construction of another Chinese cosmodrome, the fourth one (the first three were created primarily for military purposes and no longer meet the requirements of the time). The new space launch complex Wenchang should become the “Chinese Cape Canaveral”—here it is planned to build several launch pads and a “space tourist center”. Tourists, who are expected to be many, including from abroad, will be able to admire rocket launches and visit a theme park with a museum, attractions, and even orbital flight simulators.

The cosmodrome is being built specifically for launching Chinese heavy rockets of the new generation “Long March 5”. These powerful carriers, designed to take the place of the main “workhorse” for the ambitious space program of the PRC, will be delivered to Wenchang by sea directly from the manufacturer of space equipment in the city of Tianjin.

“The new generation of the ‘Long March’ carrier is not the only most modern rocket system in China. They are already creating their own reusable spacecraft,” says Trivedi. Regional press is full of information that Beijing is conducting atmospheric tests of the model of the reusable spaceplane “Shenlong”. Despite the fact that China extremely dosed distributes information about this project, it is clear that it is still far from creating a full-fledged Chinese “shuttle”, notes Trivedi. This means that for the next decades, “Long March 5” will remain the leading Chinese rocket, it is it that should ensure China’s claims to develop its own lunar program, research of near and far space.

But the main thing is that the new carrier rocket should strengthen the positions of the PRC in the international market of commercial space launches.

Perhaps initially for Beijing, the question of state prestige was really important, however now in the PRC, they increasingly talk about commercial space. It is clear, for example, that places on board its orbital station the PRC will provide to foreigners not for free. In addition, China intends to take leading positions in the field of commercial launches.

The first foreign satellite was launched using a Chinese carrier rocket back in 1987, and from 2005 such launches became regular: rockets from the PRC launch satellites from Venezuela, Nigeria, Pakistan, other countries into orbit. It is reported that by 2020, when new carrier rockets come into operation widely, the PRC intends to capture a 15-percent share in this market. And this is just the beginning.

Another commercial project of Chinese space, which the new generation rockets should ensure, is the satellite navigation system “Beidou” (BeiDou—”Big Dipper”). China intends to push the already existing similar systems: the American GPS and the Russian GLONASS. The project is already working in full swing: since 2012, the system with 16 satellites provides navigation services in the territory from China to Australia, and by 2020, the orbital grouping “Beidou” should grow to 35 apparatus and become a global system.

China also plans to promote its new rockets and ships as an alternative to Russian “Soyuz” for ensuring the operation of the ISS. In the West, many believe that connecting the PRC to space cooperation with the USA will allow depriving Russia of the monopoly on manned launches, which it received after the termination of the shuttle program. The propagandist of this idea is, for example, the famous American astronaut of Chinese origin Leroy Chiao. “China is the only power, besides Russia, that can now send astronauts into space,” he reminded in a recent interview with Forbes.

For more on Asian space programs, check [Link to related BRICS article].

Vyomanauts at the Start

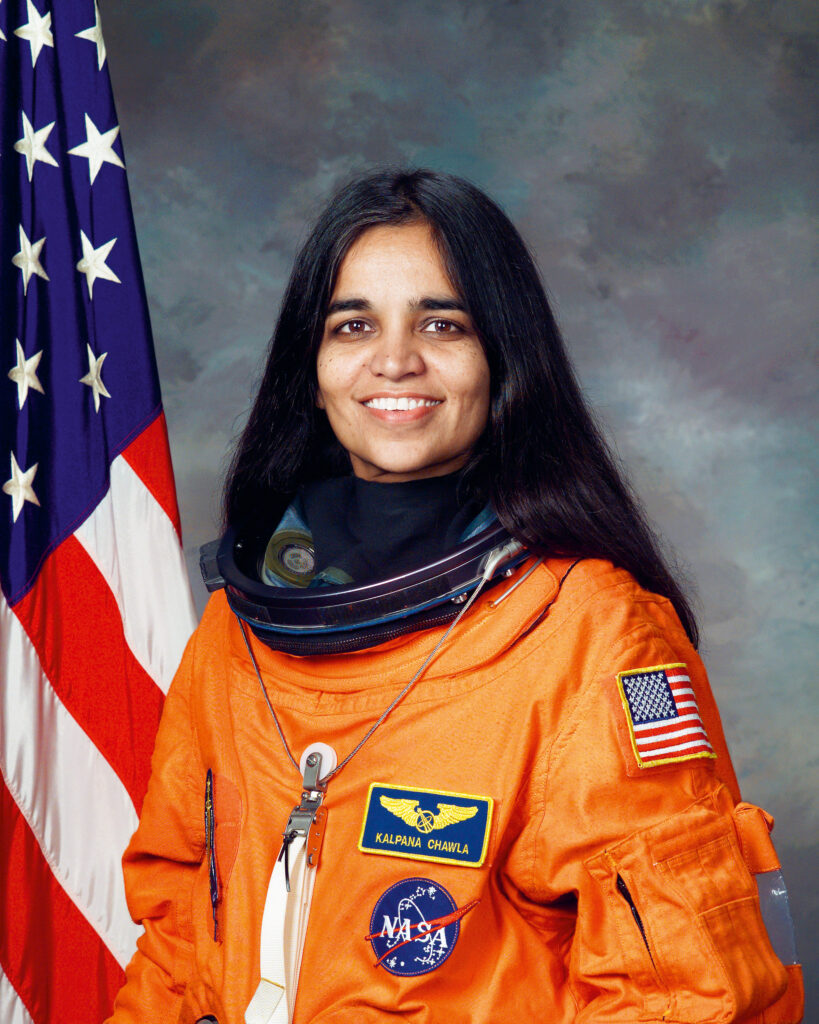

The Indian Elephant is still lagging behind the Dragon in manned flights. The country with a population of 1.2 billion people so far has only one official cosmonaut—this is Rakesh Sharma, who was in orbit as part of the crew of the Soviet ship “Soyuz T-11” in 1984—30 years ago. The Indians, however, consider “their own” the woman-astronaut Kalpana Chawla. She was born in India, but then moved to the USA, where she received citizenship and became a NASA employee. Chawla turned out to be the second native of India to fly into space—her first flight took place in 1997 on board the shuttle “Columbia”. The next one, on the same ship, ended in tragedy. In 2003, Chawla and all members of the “Columbia” crew died in the shuttle catastrophe upon its entry into dense atmospheric layers.

India for a long time did not too actively develop a manned space program, concentrating on satellites. But everything changed after a Chinese taikonaut went into space. In India, there was a big noise in the media then. The public began to demand from the authorities to “reduce the lag” from the PRC, and the opposition talked about the fall of the country’s prestige. And the authorities in New Delhi decided that the desired status of a great power requires its own cosmonauts. In 2006, a historic meeting of the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) took place, at which it was decided to activate the manned program and send a manned ship into space in a short time.

The goal of the program is to create a manned capsule for two cosmonauts, capable of staying in orbit for at least a week and returning to Earth. It is planned that the landing module will splash down in the Bay of Bengal in the area of the Eastern coast of India. For the program, its own Indian rocket-carrier GSLV MkIII will be used, which will employ cryogenic engines of Indian development.

In August of this year, ISRO head Koppillil Radhakrishnan reported that India will be able to send an Indian crew into orbit independently soon. “A full-scale unmanned module is already being prepared for an experimental launch on the GSLV MkIII rocket. The purpose of the flight is to understand the ballistic characteristics of the module for its return,” Radhakrishnan stated then.

The exact date of the manned flight was still not named. However, in local media, they express hope that the Indian crew will ascend to orbit before 2020.

Meanwhile, in India, there is an active discussion on how the space travelers representing “the largest democracy in the world” will be called. Philologists have sat down for ancient texts in Sanskrit, trying to pick up a suitable term. First, the variant “akashagami” (“the one who rides the sky”) appeared. Then the names “gaganaut” (from “gagana”—”heavens”) and “antariksha yatri” (from “antariksha”—”sky above Earth” and “yatri”—”traveler”) gained great popularity in Indian media. But lately, the term “vyomanaut” (from “vyoma”—”space”) is used more often. The discussion, however, continues.

It is also reported that the creation of space suits is already underway, and a company from the city of Mysore has begun developing special nutrition for Indian cosmonauts.

But while vyomanauts are still waiting for their turn, Indian automatic satellites and stations are already actively flying through the Solar System. So, at the end of September, the Indian research station “Mangalyaan” of the “Mars Orbiter” project, launched in November 2013, approached Mars. Thus, ISRO became the sixth space agency in the world to send its own research station to the Red Planet. “And if everything goes well, then India will become the first country for which this (to put an automatic apparatus into Martian orbit.—Ed.) succeeded on the first attempt,” Radhakrishnan proudly noted.

In 2008, the Indian lunar mission “Chandrayaan-1” started—the automatic station entered circumlunar orbit and worked for 312 days, sending an impact probe to the Earth’s satellite. The mission “Chandrayaan-2” is being prepared, during which a landing of a research apparatus on the Moon and even a small lunar rover is planned. Initially, this program was planned as a joint project with the Russian Space Agency. However, lately, India says that it intends to cope independently. The start of the interplanetary station to the Moon is preliminarily planned for 2016.

Special attention is paid by local specialists to commercial satellite launches: India has long become an active player in this market and has already sent several dozen satellites into space on orders from Germany, Israel, South Korea, Singapore, other countries. In June of this year, an Indian rocket that took off from the Satish Dhawan cosmodrome on Sriharikota Island launched five foreign spacecraft at once, belonging to companies from France, Germany, Canada, and Singapore. New Delhi intends to sharply increase the number of such launches within five years.

In addition, looking at China, India began in 2006 to develop its own satellite navigation system IRNSS. The first two satellites of this system, which should first cover India itself and adjacent states, have already been launched into orbit—in 2013 and 2014. “India traditionally initially lags behind China, as it was, for example, with the development of the national nuclear program—the atomic bomb Beijing acquired earlier than New Delhi. It was the same with the construction of its own long-range ballistic missiles, aircraft carriers or submarines,” reminds Trivedi. “It turned out the same with space, but history shows that India then always catches up.” Whether it will work this time—the future will show. One thing is clear: the long-standing rivalry between India and China is acquiring a new, cosmic scale.

According to IMF reports on emerging space economies, such competitions drive innovation .

In conclusion, the China India space rivalry underscores advancements in Asian space programs, with both nations pursuing ambitious lunar missions and commercial space launches within the BRICS framework.